Over 20 years of tasting together

Posted on January 17, 2026

First growths and more, including 1966 vintage Port

By Panos Kakaviatos for Wine Chronicles

17 January 2026

Some dinners are memorable for the bottles. Others linger because of the company. Few manage both, while reminding you why you started cellaring wine in the first place.

At 1789 in Georgetown, ten friends gathered for a bring-your-own dinner that quietly marked over two decades of shared tastings in Washington D.C. We had met at many restaurants for wine dinners, some no longer existing, others thriving. No theme was formally announced, this time, yet the evening naturally gravitated toward top-tier Bordeaux, framed by serious Champagne at the outset and dignified sweetness at the close. Each guest arrived with a bottle or two, trusting the table, the food, and the accumulated experience of years spent opening wines together.

Chris Bublitz, who brought the 1966 Port, and Kevin Shin, who brought the 1979 Ausone

The restaurant played its role perfectly. Service was attentive but never intrusive; pacing was calm, unforced, and clearly attuned to the demands of mature bottles. The kitchen showed admirable restraint, allowing the wines to lead rather than compete.

Opening the evening, Domaine Les Monts Fournois “Montagne” 2013 offered a fascinating interplay between freshness and gentle oxidative complexity. The Comtes de Champagne Taittinger Rosé 1996 at first had some musty aspects that quickly dissipated to reveal soft elegance, tertiary aspects combined with strawberry. I liked the wine increasingly – and by the time most guests had left, I tasted it again and loved it! The Krug Vintage 1995 followed with authority: architectural, powerful, and unapologetically structured before an excellent Grand Cru Robert Weil Riesling Kiedrich Gräfenberg 2021 bridged the transition into reds, pairing seamlessly with the Wagyu tartare combined with black garlic aioli, quail egg and dill. Crisp Rheingau Riesling clarity proved an excellent balance to the steak.

The Bordeaux sequence told a story of time and truth.

Château Ausone 1979 charmed aromatically despite its modest length. It reflected a bygone era when Pascal Delbeck ran winemaking at this storied Saint Emilion. Robert Parker never liked the wines crafted by Delbeck, but this 1979 stood the test of time, pairing especially well with the truffle risotto. We had much anticipation from the Lafite Rothschild

1976, but it had sadly passed its moment, while the Château Ausone 1999 showed youthful richness and promise, reflecting an oakier style four years into the Vauthier era. I did not particularly like it, as later showings from Vauthier are better balanced between oak and ripeness, but still an excellent wine. A blind Montelena Cabernet Sauvignon 1997 surprised many, mistaken for Spain, yet proving its classical Napa credentials. Kevin Shin was – as ever – on the ball here, noting less acidity than an Old-World wine. It was very enjoyable, and logic should have led us to guess: 1976 Judgment of Paris, and here we are in … 2026!

1976, but it had sadly passed its moment, while the Château Ausone 1999 showed youthful richness and promise, reflecting an oakier style four years into the Vauthier era. I did not particularly like it, as later showings from Vauthier are better balanced between oak and ripeness, but still an excellent wine. A blind Montelena Cabernet Sauvignon 1997 surprised many, mistaken for Spain, yet proving its classical Napa credentials. Kevin Shin was – as ever – on the ball here, noting less acidity than an Old-World wine. It was very enjoyable, and logic should have led us to guess: 1976 Judgment of Paris, and here we are in … 2026!

The second red flight sharpened distinctions: Château Latour 1995 – blending 74% Cabernet Sauvignon, 22% Merlot 22%, 3% Cabernet Franc and 1% Petit Verdot – impressed with poise, coming across more supple than powerful, and thoroughly enjoyable! The 1995 vintage was sometimes a mixed bag in Bordeaux, welcome after several tough vintages (1991, 1992, 1993, even 1994), but Latour proved superb.

Quite a lineup!

Château Margaux 1999 emerged as a model of seamless elegance. I had enjoyed another bottle of this same vintage but two weeks earlier, and this bottle proved just as good! Deep red, it opens with black currant and blackberry, accentuated with floral aromatics and licorice. More fill than medium-bodied, I really liked the precision and depth of the wine, balancing acidity and richness – almost effortlessly – with not yet fully resolved tannins (good for future cellaring) that exude seamless texture. Long finish. Although I could just enjoy this wine alone, it paired nicely with the New York Strip and purée of potato.

Graves, with no less than four wines from Domaine Clarence Dillon, delivered an emotional summit. Château Haut-Brion 1995 was linear and intellectual – a very good wine that split opinions over dinner – but most agreed that the 1998 proved transcendent: minty, smoky, refined, and resonant. Château La Mission Haut-Brion 2000 rivalled the greatness of the 1998, reflecting more coiled-in power plus elegance. Along with the Haut Brion 1998, the wine of the night, perhaps just a bit better than the Margaux 1999. As for the La Mission Haut Brion 2005, it remains a study in patience – and a great wine in the making!

The evening closed with a magnificent Fonseca Vintage Port 1966. The brown rim reflected its nearly 60 years, but it tasted more youthful than the years would suggest, still reflecting touches of damson and red berry fruit, along with far more pronounced tertiary notes of orange peel, dry fig, subtle spices – and, especially, fine espresso. The overall impression is that of a refined and composed wine that also is deeply expressive. It paired well with the cheeses but honestly, just drinking it on its own offered much pleasure. It was followed by a radiant Haart Piesporter Goldtröpfchen Beerenauslese 2015.

This was not a night of trophy hunting. It was a night of listening: to the wines, to time, and (especially) to friendship. Such evenings remind us why wine matters.

Margaux, Latour, Trotanoy and so much more

Posted on January 5, 2026

New Year Wine Dinner with Friends

By Panos Kakaviatos for Wine Chronicles

5 January 2026

Thanks to Tamar and Keith Levenberg for hosting an excellent dinner with Maureen Nelson, Joel Davidson and myself. I had not seen Maureen in ages, so it was especially great to see her: You haven’t changed one bit, Maureen! Each of us brought some fine wines to share.

We opened mostly Bordeaux. Since I am in Alsace, I also brought a Domaine Trimbach Clos Sainte Hune Riesling 2002 (96) to start things. I had purchased it from the winery upon release. It had a dark straw color, but never you mind: not a hint of oxidation. Although a bit musty upon opening, normal after being cooped up in a bottle for nearly 23 years, that blew off after I double decanted. Double decant a dry white, you may be asking? That can be useful, I say!

Properly aged Riesling, double decanted 😉

A somewhat soft spoken Riesling, as Clos Sainte Hune can pack more power. Medium bodied, but it builds, beckoning further drinking. The balance between 4.2 grams per liter of residual sugar and 9 grams of total acidity left a dry impression, with lemon peel, white stone fruit, and hints of wet earth but not “old” tasting. That last aspect merely added complexity to the picture. Over three hours later, for the cheese course, we returned to the wine, which was not put on ice or in the fridge, and I dare say that it improved with respect to freshness and vibrancy. The palate felt suave and smooth. A long, albeit subtle finish. Not powerful or intense, but subtle. A friend tells me that he refuses to serve quality Riesling unless at least 21 years old, and this 23-year-old wine proved his point. The estate dubs 2002 as an “outstanding vintage, especially for Riesling”. The alcohol clocks in at 13%.

Clos Sainte Hune has 1.67 hectares under vine on stony argilo-calcaire, or Muschelkalk, limestone terroir, exclusively planted in Riesling, and located in the heart of Grand Cru Rosacker, in Hunawihr. The limestone soil allows this Riesling to develop a specific aroma and a wonderful concentration of fruits. Dry yet succulent, of phenomenal complexity, this wine develops an extraordinary aftertaste of wet stone after a few years in bottle. The plot, which is approximately 50 to 70 years old, is south south east exposed and the yields are low. Annual production reaches about 9,000 bottles, depending on the vintage.

As tasty as it looks: Bravo Keith!

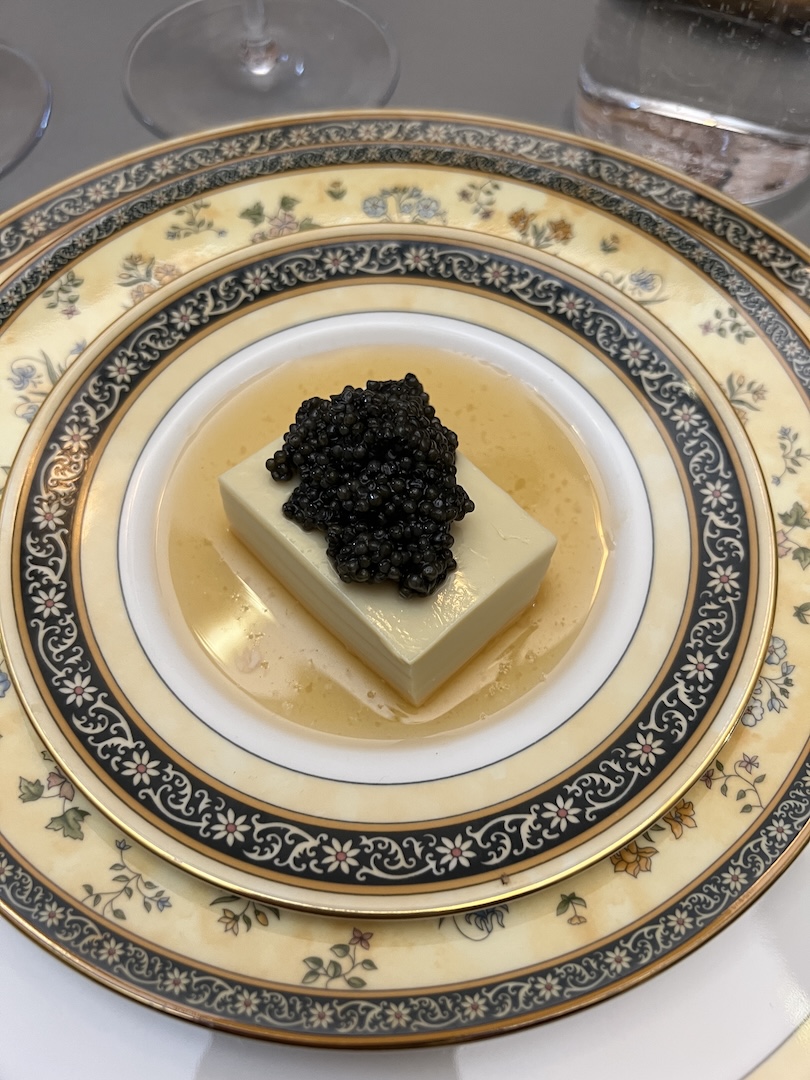

Thanks to our wonderful hosts for superb salami and foie gras, French bread, and caviar atop Tamago tofu, also known as egg tofu, which is a popular Japanese custard made from eggs and dashi (Japanese soup stock), not soybeans. Its name comes from the smooth, silken texture and square shape, which resembles traditional tofu. All of the above went especially well with the Clos Sainte Hune.

Thanks to Maureen Nelson, we kicked off with an excellent Les Forts de Latour 2000 (94), the second wine of Château Latour. What struck me was the youthful blueberry cool fruit and cassis, delivered smooth. A pristine expression not too tertiary but with hints of cigar box and plenty of plum like richness and excellent integration of the new oak. Shortly after release, the celebrated critic Robert Parker said that this second wine would evolve for about 15 years, but it is firmly in a pleasing drinking window at about 25 years in bottle, no doubt (at all) due to the unhurried ripening period of the 2000 vintage, plus an Indian summer that led to optimal harvest conditions, reflecting balance and poise.

Les Forts 2000 performed very well in this lineup!

Did you know that the wine was first labelled with this name in 1966? Grapes come from the edge of the famous Enclos at Latour and from plots located outside the Enclos, in Cru Classé areas of Pauillac such as Piñada, Petit Batailley and St. Anne, which have belonged to the estate for more than a century and whose vines benefit from a high average age (around 40 years). Furthermore some plots that could be used in the Grand Vin may finally be included in the Forts de Latour blend, depending on how their quality is judged during the blending tastings. Les Forts de Latour is produced with the same care as the Château Latour, both in the vineyard and in the winery. One main difference, apart from grape origin, is a lower proportion of new barrels – between 50 to 60% – for aging. The blend for Forts de Latour also varies from one year to the next, but there is almost always a higher proportion of Merlot (25 to 30%) compared to the Grand Vin. Not sure about the exact blend for the 2000.

Latour and Margaux: 1999

We then tried the Château Latour 1999 (93), which I had purchased shortly after release, from a French merchant. It is interesting to note that Robert Parker dubbed the 1999 Latour “exceptional” for the vintage, a “modern day version of Latour’s magnificent 1962 or 1971” when he tasted the wine from barrel. Just over 25 years later, what’s the verdict? I had double decanted the wine four hours before it was served over Keith’s amazingly delicious filet mignon of elk (accompanied by equally fabulous and silky smooth purée de pommes de terre and haricots).

It is a good idea to aerate a wine of 25 years, to allow for any stuffy aromas to dissipate, and they did. The wine revealed quite a lot of fruit but also high-toned acidity that left its mark, in contrast to the more supple and richer Les Forts from the superior 2000 vintage. Over time, the 1999 exhibited floral and fresh meadow tertiary notes, as well as the telltale Pauillac graphite. While the 2000 showed fuller body and superior richness, I grew to enjoy the linearity of the 1999 Grand Vin. It had a longer finish, its inherent tension matching the richness of the elk nicely, but was not quite as good as the Forts de Latour from the 2000 vintage.

Which one was better?

About 1999

Why the 1999? Joel brought the Château Margaux 1999, so I thought it would be fun to compare the two First Growths from that vintage. While 2000 is seen as an exceptional vintage, especially in the Médoc, 1999 proved more challenging, taking a clear back seat to the 2000 due to unpredictable growing conditions: In August 1999, the outlook was reasonable despite a hurricane early in the season and wet weather late in the Spring. Then rain storms hit with a vengeance. Because we also enjoyed the Château Margaux 1999, I tried to look up precise station rain totals for Margaux vs. Pauillac in 1999, but they aren’t easily available online. I think that terroir differences support the idea that Margaux “withstood” the heavy late season rainfall better than Pauillac/Latour. So even if actual rain totals weren’t wildly different between the northern and southern Médoc in 1999, Margaux soils likely coped better with late showers, potentially preserving sugar accumulation and limiting dilution effects compared to Pauillac/Latour. Indeed, Château Latour displays deep, dense layers of coarse gravel on a subsoil of clay and marl while Château Margaux shows thinner, more superficial and finer gravel mixed with varying amounts of sand, limestone, chalk, and clay.

Filet mignon of elf, from the barbecue and topped with truffle butter, paired with oh so silky smooth purée de pomme de terre and savory green beans.

Château Margaux 1999 (96) – I recall first encountering this wine at the château with fellow wine aficionado Frédéric Lot, after it had just been bottled, back in 2001 during a visit to the estate, along with 1997, 1998 and 2000 – then a barrel sample. While the 2000 showed the most promise back then, the 1999 was my second favorite, followed by the (then) more charming 1997 and finally the (then) rather closed 1998. More recently, some seven years ago, over a vertical at Taberna Del Alabardero in Washington D.C., I rated it 94 as yielding a fresh bouquet of spring flowers and bergamot tea along with a touch of wet earth, the palate (then) lovely in its elegance, easy to drink, even though lacking the backbone of the 1996, which had been tasted alongside.

Oui, c’est magnifique ce Margaux 1999

But chez Keith and Tamar, the wine had just been popped and poured, unlike the double-decanted Latour 1999. From the start, it displayed impressive palate depth, more so than the Latour 1999, which was medium-bodied compared to Margaux’s more full bodied aspect. The Margaux also displayed better focused red and black berry fruit, furthermore leading to wonderful crushed mint and tobacco expressions on the long finish. In a review from 2022, William Kelly compared it to the 1985 vintage, and that is quite a compliment. I can see why. I really liked the 1999 Margaux this time.

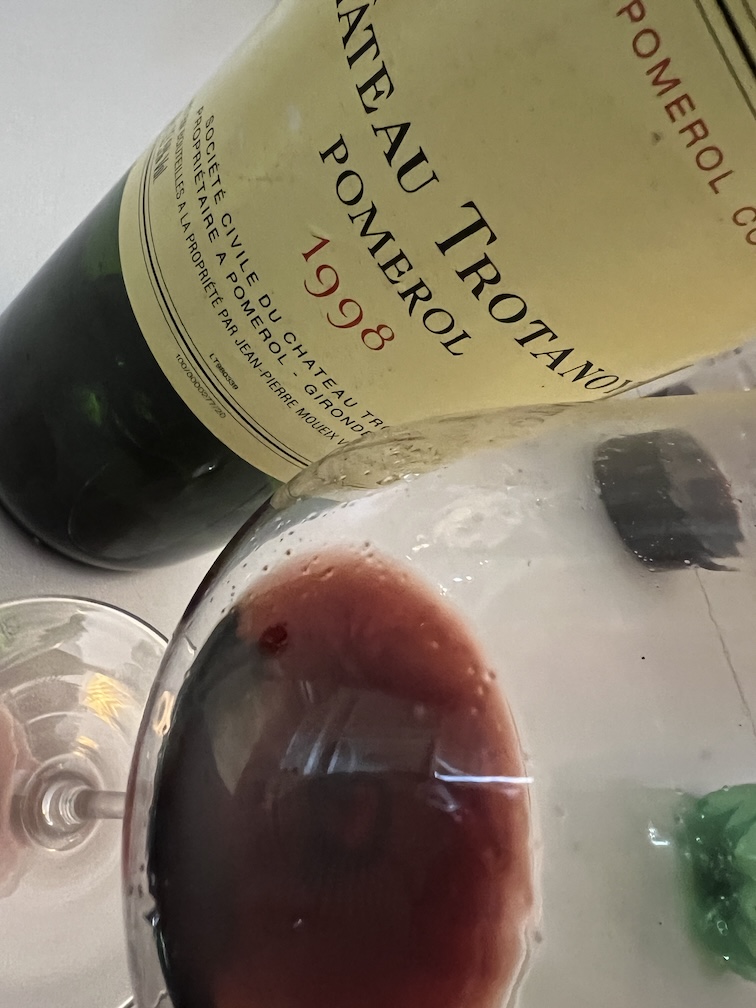

Ozzy, the most discerning among us

Château Trotanoy 1998 (97) – Thanks to Keith, this majestic wine also was served, and I immediately loved it, also as a superlative pairing to the elk filet. Trotanoy can be like Léoville Las Cases: it can take a long time to open up, but by Golly in January 2026, the wine sang. It stole the red wine show with mellowed power, sophisticated richness and suave tannin and fine dark chocolate notes along with Médoc-like graphite. A wine of layered polish, not gloss. With time in glass, it only improved. And consider just how good 1998 was for Merlot-dominant wines in Pomerol: powerful, concentrated, tannic, and long-lived reds with rich dark fruit and spice. After nearly 27 years in bottle, Trotanoy has entered an early drinking window. Yes, early! Many critics say that 1998 counts as one of the greatest Right Bank vintages ever. It is most certainly a benchmark vintage.

Fabulous, with upside potential !

Jean-Pierre Moueix purchased the estate in 1953, but Château Trotanoy has been considered one of the premier crus of Pomerol since the end of the 18th century. The soil of Château Trotanoy is a combination of gravel and very dense clay which tends to solidify as it dries out after rain to an almost concrete-like hardness, hence the name “Trotanoy,” which can mean “too wearisome” in French. The Trotanoy vineyard slopes gently to the west. The soil at the highest point of exposure contains a good proportion of gravel, becoming progressively more dominated by clay as the elevation declines.

Happy crew ringing in 2026 with great food and wine!

Under this clay is a subsoil of red gravel and an impermeable layer of hard, iron-rich soil known as crasse de fer. This soil diversity brings power, depth and complexity to the wine. Trotanoy is vinified in small concrete vats, while aging takes place in oak barrels, about 50% new oak. Trotanoy is a naturally profound, complex, richly-concentrated wine with outstanding aging potential, proven in this 1998. The wine possesses a deep color and a dense, powerful nose, repeated on the palate with the addition of creamy, dark chocolate notes, and a singular concentration of flavor owed to its very old vines.

A final red, vintage 1945

Keith and I have been trying to source a bottle of Château Mouton Rothschild 1945 and share the cost among several wine pals, but it is evidently not an easy task. And what happens when one purchases such an old bottle and then encounters a cork or other problem? Keith sourced a Baron Philippe wine from the 1945 vintage, coming from, as the label indicates, the best vines of the former Mouton d’Armailhac vineyards. Much of the vines used to craft the bottle that Keith opened for us – the Château Mouton Baron Philippe 1945 vintage – would later be used for what has come to be known today as Château d’Armailhac. Upon opening I was struck by almost salty taffy aromas, not unappealing, and actually quite intriguing. The palate was more aggressive in nature and quite acidic. The wine, alas, was past due, as can happen with such old bottles. But kudos to Keith for bringing this to the table, as the label is gorgeous!

Wonderful cheese plate!

Château Climens Barsac 1988 (97) – For the superb assortment of cheeses, we enjoyed both the Clos Sainte Hune but also – especially with the blue type cheeses – the exceptional Climens from Barsac. I have always loved this wine, and thanks to Maureen for the half bottle, which did not disappoint. Time in glass yielded vivid notes of candied orange peel, crème brûlée, black tea and subtle ginger from the botrytis (noble rot).

Great combo!

The 1988 vintage in Barsac (and Sauternes) was outstanding, considered one of the best of the late 1980s, marked by excellent noble rot developing later in October after a warm and dry September, leading to rich, honeyed, and complex sweet wines with great acidity and aging potential. Château Climens along with Coutet produced great wines from Barsac in that vintage, still vibrant today, as proven over this dinner. And thanks to Keith and Tamara for the intensely delicious chocolate cake, which also paired well with the Barsac.

All in all, a great evening!

Revisiting Weingut Bernhard Huber

Posted on December 29, 2025

Malterdingen, Baden-Württemberg: Burgundy Precision, Baden Soul

By Panos Kakaviatos for Wine Chronicles

29 December 2025

A visit to Weingut Bernhard Huber in Malterdingen is never just a tasting; it is a lesson in continuity, restraint, and conviction. I visited the estate on 11 November, in the calm that follows harvest – and a bank holiday in France. Julian Huber was not present that day, but a highly accomplished sommelier from the estate welcomed a friend and me, guiding us through an impressively broad and revealing lineup.

Few German wineries have shaped the modern understanding of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay as profoundly as Huber. Bernhard Huber was among the first to demonstrate that Germany could produce Pinot Noirs of genuine gravitas and longevity, not by chasing ripeness, but by embracing structure, restraint, and terroir. Bernhard’s frequent exchanges with Burgundy and his refusal to follow trends allowed him, already in the early 1990s, to craft wines that stood apart at a time when many sought power over precision.

When Julian Huber took over in 2014, aged just 24, expectations were daunting. A decade later, it is clear that he has not merely preserved his father’s legacy but sharpened it. Burgundy remains a reference point, but the wines today speak more clearly of Malterdingen, Bienenberg, Sommerhalde or Schlossberg than of any external model. The stylistic evolution is subtle but decisive: less overt oak, cooler fruit profiles, more reduction, and a striking sense of tension and salinity across both reds and whites.

The estate now harvests around 35 hectares, predominantly in Pinot Noir, rooted in weathered shell limestone soils that echo the Côte d’Or in their ability to confer finesse and longevity. Vineyard work is paramount, yields are modest, and sélection massale is used to refine the finest parcels. Grape variety has largely disappeared from labels: here, place matters more than nomenclature.

In the Glass: A Tasting Snapshot (11 November)

Excellent, traditional method bubbly

The tasting opened with their traditional method bubbly Blanc de Noirs, creamy yet precise, offering quiet depth rather than overt fruit. The dry rosé, produced since 2020 but pointedly without the word “rosé” on the label, underlined Huber’s philosophy: this is a terroir wine, smoky, reductive, and structured, aged 14 months in barrel with one-third new oak: decidedly not a casual summer pour.

We tasted through wines from the 2023 vintage, which, we learned, was warm and healthy overall, but punctuated by rain just before and during harvest. Larger berries and thinner skins brought mildew concerns, yet the finished wines show admirable clarity and balance rather than dilution.

Among the Pinots, the Malterdingen Ortswein (white label, red capsule) offered a classic, poised expression: fine red fruit, moderate alcohol (13%), and impressive depth for vines averaging 25 years. The step up to Alte Reben (red label) was immediate: older vines (around 45 years), lower yields, greater textural depth, spice, and tannic presence, still framed by Malterdingen’s signature finesse. Oak remains measured at one-third new, notably less than under Bernhard. The estate boasts many great growths, the equivalent of grands crus, designated in German as Grosses Gewächs or GG.

Whether a premier cru or GG level, distinctions sharpened. And I love the graphic design sense of the estate: white labels designate regions, while the red labels designate more premium level wines at village, premier cru or GG grand cru. Same for the whites, only labels for premium level wines are green.

-

The Bienenberg GG was beguiling yet reserved, with more acidity, limestone-driven structure, and a flirtatious nose that belied a tightly wound palate demanding cellar time.

-

The Köndringen, from younger Pinot Noir vines planted in 2018, was muscular and wind-swept, with spice, firm tannins, and a touch of bitterness.

-

The Sommerhalde GG on red clay and limestone near the Black Forest at 350 metres in elevation showed wonderful balance and poise, though extraction here requires a careful hand.

-

The Hecklingen, tasted from its very first vintage in 2023, felt frank but still finding its voice: tighter and more astringent than Alte Reben at the same price point.

Then came the standout: the Schlossberg GG. From an extraordinarily steep, wind-exposed slope, yields of just 25 hl/ha and production of roughly 1,500 bottles, this was a wine of rare harmony. It was airy yet substantial, with bright red cherry fruit wrapped in limestone freshness, tannins present but already spherical. A wine that feels both light and profound, and unmistakably complete.

The Whites: Quiet Authority

Chardonnay has been part of the Huber story since the late 1990s, and today it sits firmly among Germany’s benchmarks. The Malterdingen Chardonnay—direct pressed, unfiltered, minimal bâtonnage—was saline, mineral, linear yet generous, already sold out at the time of my visit. The Alte Reben Chardonnay in a gorgeous green label followed with Meursault-like breadth: buttery but precise, long, and quietly powerful (12.5%). Julian’s affection for Burgundy is no secret. His dog is named Perry, after Meursault’s Perrières.

For optimal price/quality ratios, the Alte Reben (old vines) in both Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, is an excellent choice!

At the top, Bienenberg GG Chardonnay showed greater reduction and acidity, white florals and chamomile, while Schlossberg GG Chardonnay took everything (yet again) a step further: crystalline, herbal, intensely saline, with remarkable length and composure. These are wines built not for immediate charm but for evolution.

A brief aside worth noting: the Breisgau cuvée (50% Pinot Blanc, 50% Pinot Gris), now in its third vintage, displayed what sommeliers aptly call the “Huber nose”—reductive, precise, and disciplined. Pinot Gris is picked early to avoid heaviness, resulting in a taut, gastronomic white of real interest.

A World-Class Estate, Quietly So

This was not my first encounter with the Huber estate. I first visited Wildenstein in 2014, walking the limestone-over-clay slopes with Bernhard Huber himself, just months before his passing. As I wrote at the time, one cannot help but notice the rocky surface and pronounced incline of this extraordinary site—a place that feels closer to Burgundy than to most preconceived notions of German red wine. Bernhard reminded me then that it was Cistercian monks who first planted Pinot Noir here, centuries earlier, laying the foundations for what would become one of Germany’s most revered vineyards. Wildenstein, just two hectares in size, was already widely regarded as producing arguably the finest Pinot Noir in the country, irrespective of price.

Historical records dating back to 1285 attest to Pinot Noir plantings known as “Malterdinger”, named after the village that remains the heart of the estate today. The continuity is striking. The vineyards have been in the Huber family for generations, but it was Bernhard and his wife Barbara, upon taking over in 1987, who began estate bottling under their own name. Until then, grapes and wine had been sold to a local cooperative. That decision—to bottle, to define a style, to look to Burgundy not for imitation but for inspiration—changed the trajectory not only of the estate, but of German Pinot Noir more broadly.

That 2014 visit remains vivid in my memory. Bernhard was generous with his time, walking me through the vineyards and later insisting we sit down for lunch, to taste the wines in their proper setting, as he put it—at table, with food, and without haste. Returning now, a decade later, tasting through the range under Julian’s stewardship, the sense of continuity is unmistakable. The wines have evolved, sharpened, and gained tension, but the foundations laid by Bernhard with patience, humility before terroir, and an unshakeable belief in Pinot Noir, remain firmly intact.

Around 90% of Huber’s production remains in Germany, and it is hard to find! Most wines at the estate were already sold out. Some are exported, particularly to Scandinavia, a market that is growing steadily. Demand far exceeds supply, especially for the Chardonnays and GGs, yet the estate resists hype. What defines Huber today is not ambition for expansion, but an unwavering commitment to style.

As Julian Huber has said, wines here are not meant to impress instantly, but to reveal themselves over time. Tasting across the range in November, that philosophy felt not like dogma, but lived experience. These are wines of discipline, restraint, and inner confidence: Burgundian in method, unmistakably Baden in soul.

Few estates pursue their vision with such consistency. Even fewer succeed so completely.

What’s in a Name?

Posted on December 27, 2025

Why wine origin still matters

By Panos Kakaviatos for Wine Chronicles

27 December 2025

Every so often, the wine world is reminded that names are not neutral. They carry weight, memory, and meaning that must be defended.

Just before Christmas, Burgundy’s trade body, the Comité des Vins de Bourgogne, intervened after a major discount retailer aired a radio advertisement promoting a low-priced wine from the IGP Pays d’Oc. The advert praised the wine by evoking “this Burgundian grape with hazelnut aromas”, a formulation clearly designed to borrow the reputation of Burgundy while selling a wine with no geographical or cultural link to it. Within days, the campaign was withdrawn.

At first glance, this may seem like an overreaction. After all, Chardonnay is grown worldwide, right? From Napa to New Zealand, by way of Germany to South Africa. But Burgundy’s response was not about a grape name. It was about origin, precision, and the protection of a system that gives wine its meaning.

Take the bottle illustrated here: Chablis Grand Cru La Moutonne 2009, Domaine Long-Depaquit. Yes, it is Chardonnay — but that is only the beginning of the story. It is Chablis, a distinct appellation within Burgundy. More than that, it comes from a single, historic Grand Cru vineyard site, La Moutonne, uniquely positioned between Les Preuses and Vaudésir, and long recognised for its singular expression. Domaine Long-Depaquit, based in the heart of Chablis, farms some 65 hectares, including five Premier Crus and five Grand Crus, each with its own identity, exposure, soils, and voice.

This is what the appellation system exists to protect: not abstractions, but layers of specificity. Place within place. Within place! Climate, slope, geology, history, human interpretation. Burgundy is not Burgundy because it grows Chardonnay; it is Burgundy because Chardonnay grown there tastes like nowhere else.

When a mass-market wine uses Burgundy’s reputation as a convenient flavour cue, it flattens all of this complexity into a marketing shortcut. That is why the Burgundy Wine Council reacted so strongly. It was not out of arrogance, but out of necessity. Once meaning is diluted, it is difficult to restore.

The same logic applies beyond Burgundy. Champagne is not a synonym for sparkling wine. Porto is not a style descriptor. Barolo is not a generic red. These names are legally protected because they correspond to real places and collective histories. They also protect the consumer, who has every right to expect that a reference to a region implies more than a vague stylistic suggestion.

In an era when wine is increasingly marketed like any other fast-moving consumer good, the temptation to “borrow” prestige remains strong, especially at the lower end of the price spectrum. But prestige in wine is not decorative. It is cumulative and shared.

So yes, this was only a radio advertisement. But it serves as a useful reminder: in wine, names still matter. They matter because behind them lie vineyards like La Moutonne, and thousands of others, whose identity depends on respect for origin, without which wine becomes just another beverage.

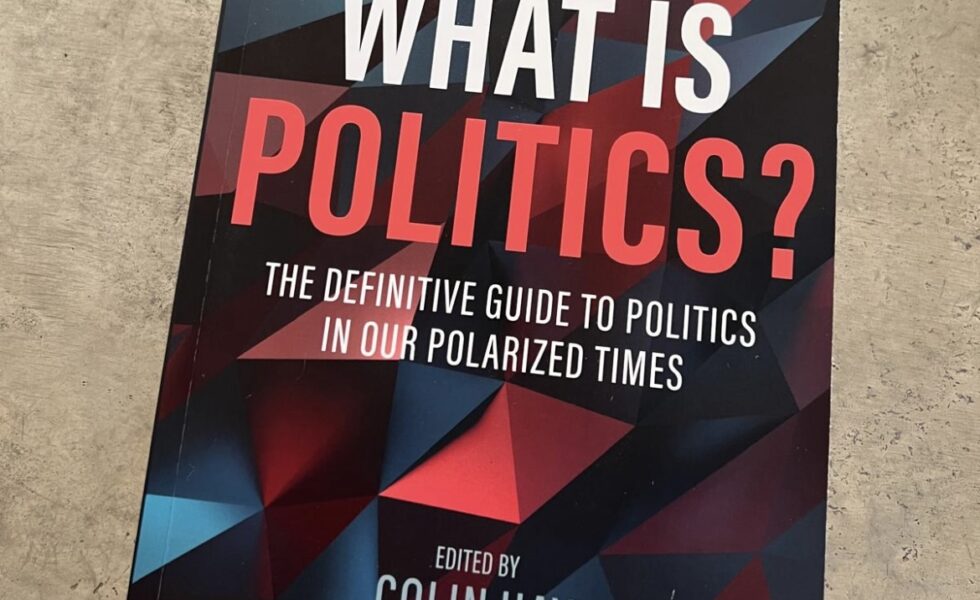

What Is Politics?

Posted on December 26, 2025

Reading a friend’s book, thinking politically

Book review by Panos Kakaviatos

26 December 2025

There is a challenge to review a book edited by a friend, especially when that friend is a political scientist and one’s own professional life unfolds in a different, if adjacent, register.

Colin Hay and I have known each other for several years, tasting and reviewing wines in Bordeaux especially. But we both inhabit worlds that are political, though not in the same way. Colin approaches politics analytically, as a professor and theorist. I encounter it more obliquely, through media relations at the Council of Europe, and – perhaps unexpectedly – through wine writing, where questions of identity, power, tradition, and belonging are never far below the surface.

It is precisely this shared but differently practiced relationship to politics that makes What Is Politics? The Definitive Guide to Politics in Our Polarized Times such an interesting book to read from outside the academy, yet not outside politics.

Hay’s introduction sets out the intellectual ambition with characteristic clarity. Politics, he argues, is not reducible to what politicians do, nor exhausted by elections or institutions. It is a broader process of collective choice-making under conditions of contingency: conditions in which neither fate, tradition, nor technocratic management can plausibly absolve us of responsibility. This framing resonates beyond political science. Anyone who has watched cultural traditions defended, contested, rebranded, or instrumentalized (in gastronomy no less than geopolitics) will recognize the terrain.

The book’s structure reflects this expansive view. Each chapter approaches politics through a different analytical lens: power, moral choice, collective action, behaviour, identification, gender, cognition, ritual, rhetoric, crisis management. At times, the language is unapologetically technical. This is not a book that flattens political theory for ease of consumption. But its seriousness is also its virtue. It insists that how we conceptualizepolitics shapes what we expect from it, and what we excuse when it fails.

For me, the most compelling chapter is Vivienne Jabri’s “Politics as identification.” It is here that the book speaks most directly to the political moment we inhabit. Jabri explores how identities – national, ethnic, cultural, gendered – are not simply inherited facts but are produced, performed, and mobilized through practices of identification. Identity, in this sense, is not outside politics; it is one of its most powerful currencies.

What makes this chapter especially valuable is that it resists easy moral sorting. Identity politics is presented neither as progressive virtue nor as reactionary vice. It is shown instead as a political force that can enable recognition, solidarity, and resistance, but also exclusion, hierarchy, and simplification. The danger arises when identity hardens into destiny, when politics becomes a struggle over who is rather than what ought to be done.

Read this way, the chapter offers tools for understanding abuses of identity across the political spectrum. Progressive struggles for recognition can slide into moral absolutism; conservative or nationalist appeals to heritage can become civilizational dogma. In both cases, the move is the same: difference is essentialized, disagreement moralized, and politics reduced to a friend. That insight feels particularly urgent today.

Some readers may find the book’s conceptual vocabulary (gendered politics, performativity, institutionalized exclusion) more familiar or persuasive than others. The volume emerges from traditions of critical political analysis, and it does not pretend to ideological neutrality. But that, too, is part of its honesty. Like good wine writing, good political analysis is never written from nowhere. It reflects choices (of lens, emphasis, and framing) that deserve to be made visible rather than disguised.

Perhaps that is where my own reading converges with Colin’s project. Wine writing, at its best, is not just about flavour; it is about place, memory, power, legitimacy, and who gets to define value. Media relations at an institution like the Council of Europe is not simply communication; it is the careful navigation of language, identity, and representation in a crowded political space. In different ways, we are both engaged in what Hay describes as politics: making sense of collective choices under conditions of uncertainty.

What Is Politics? does not offer comfort, nor does it offer slogans. It offers something rarer: an invitation to think more carefully about the categories we use when we say something ispolitical, or insist that it is not. In polarized times, that invitation is not merely academic. It is political.

Wine Chronicles

Wine Chronicles

Recent Comments